In the closing years of the First World War, teenage French radio operator and cellist Maurice Martenot (1898-1980) noticed that his audio equipment possessed the rudiments of a musical instrument. By adjusting its dials, he could - to the fascination of his soldierly colleagues - pick out a simple melody. This realisation awoke in the young Martenot an insuppressible musical ambition, the very same which had already propelled his sisters Madeleine and Ginette towards respective careers as a musical pedagague and concert pianist. Maurice dedicated the rest of his life to using the "extreme purity of [electrical] vibration" to develop a legitimate electronic musical instrument, which he later named the ondes musicales Martenot (“musical waves Martenot”).

With the war concluded, Martenot began work on an instrument (the “model zero”), which bore little resemblance to later iterations, being practically identical to apparatus developed contemporaneously by Leon Theremin in Soviet Russia. Martenot's contraption comprised a small wooden box and metal antenna, and the player regulated the pitch from a distance, by free motion of the hands in space. Maurice concluded that this instrument was not viable, requiring near-absolute immobility and unheard of precision to play in tune.

Almost a decade later on 3 May 1928, spurred by Leon Theremin’s presentation in Paris in 1927, Martenot unveiled a much-improved instrument, the model one at the Garnier Opera House in Paris. This instrument allowed him to control pitch by means of a wire connected to ring worn on the finger. By pulling the wire longer and shorter, the performer could modify the pitch. A ruler positioned on the floor allowed tones to be found much more easily than on the theremin, while a button positioned on an adjacent table permitted control of the volume. The concert was met with widespread critical acclaim and encouraged Martenot to develop his instrument further.

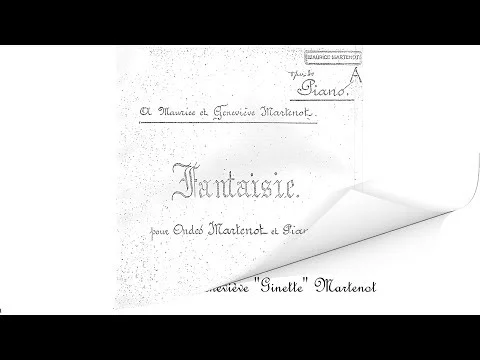

In his model two instrument, Martenot positioned the string and ring above a dummy keyboard, which eliminated the difficulties of playing in midair, while still allowing expressive and precise glissando. The model three placed the soundmaking circuitry of the instrument within an elegant cabinet housing. The instrument continued to garner attention. Composers including Dmitri Levidivis, Darius Milhaud, Jacques Ibert and Arthur Honegger began composing for the instrument, and Leopold Stokowski (who had also worked with Leon Theremin) invited Maurice and his sister Ginette to demonstrate the instrument in New York, accompanied by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. The Martenot siblings astounded not just the people of New York but those of Hawaii, Japan, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore and Java.